WILKESBORO, N.C.

If there was ever a moment the Confederacy had a chance to stop Stoneman's Raid, it was March 30 through April 1, when his cavalry was bogged down in Wilkes County by flooding and moonshine.Rebel forces concentrated in Salisbury, 60 miles southeast, were awaiting Stoneman's attack. If they had come out to meet him, who knows what might have happened. They could have delayed or prevented his invasion of Virginia, which closed the back door on Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

Given Stoneman's orders "to destroy and not to fight battles," he might not have put up much of a fight. Over half his forces were on the south side of the flooded Yadkin River, so at the very least he would have had to retreat significantly upstream to cross the river and head north to his primary targets in Virginia. Hundreds of his soldiers were in no condition to fight, after discovering some of the home brew that made Wilkes County famous.

Howard Buzby of Germantown, Pennsylvania, described the scene:

The very heavens had opened their floodgates, and the water was coming down in sheets, which accounted somewhat for the appearance of the troops on the outside, and several whisky stills, which had been struck back of the Ridge, accounted for their appearance on all sides. The number of the "wounded" was startling, and a good many were "dead," for corn whisky is fearful stuff. With the rain coming down in torrents and mud knee-deep, and the stuff warm in the stills, our brave allies were driven to drink.Fortunately for Stoneman, there was almost no local resistance. Wilkes County was known as the "little United States," and he couldn't have picked a friendlier place to be bogged down. In the 1861 secession referendum, 97 percent of Wilkes voters were loyal to the Union.

It's unlikely the Confederacy knew his exact whereabouts, much less that his forces were divided and sauced. But they had every reason to believe he was following the Yadkin to attack Salisbury, so it would not have been hard for them to find him.

At this point in the war, the rebels were more interested in defending their towns than looking for a fight. If they had counter-attacked and driven Stoneman back, they might have preserved Robert E. Lee's escape route into the Virginia mountains, saved all the supplies stockpiled at Salisbury, and given the South a much-needed moral victory. They wouldn't have changed the outcome of the war, but they probably would have extended it.

Stoneman's biographer, Ben Fuller Fordney, wrote that the general had a great fear of finding himself with his command divided by a river, subject to piecemeal attacks by the Confederates. Similar circumstances had been his undoing at Chancellorsville in 1863 and in Georgia in 1864. "He seemed to think that if the enemy came down on his side, he was a goner," Buzby said.

On April 1 or 2, the flooding finally subsided, and the south-side troops were able to cross the Yadkin. They headed north by multiple routes, and some were involved in a skirmish at Siloam on the way to Mount Airy. By April 3, they would be in southwestern Virginia, where they would be unstoppable.

Guns vs. butter, Chapter 2: 'You'll pay the devil'

A historical marker in the well-preserved antebellum village of Rockford, N.C., tells an interesting footnote, which reminds me of the story we posted back on March 26 of Gen. Stoneman taking Mrs. Councill's last firkin of butter.

Another account of this incident explains that Jasper York "was not quite normal." According to an online genealogy, Jasper was the youngest in a family of 18 children. At the time of the raid, he would have been 4 or 5 years old, his mother Nancy was 55, and his father Marcus (who also had nine children by a previous marriage) was about 85.Union Gen. George Stoneman's raiders passed through this area along the north bank of the Yadkin River on April 1-2, 1865. As they rode through Rockford, they stopped here at Mark York's tavern, a Federal-style building constructed about 1830. According to local tradition, York's wife was churning butter in the front yard with her young son, Jasper, at her side. The troopers demanded that she reveal where local residents had hidden animals and valuables when they learned of the raiders' approach. She refused to answer, even after the Federals threatened to take her son away with them, but finally retorted, "And you'll pay the devil." The soldiers gave up and left, and she returned to her churning.

York's Tavern, Rockford NC (circa 1830)

NEXT➤ Guess where North Carolina's last rebel was born

|

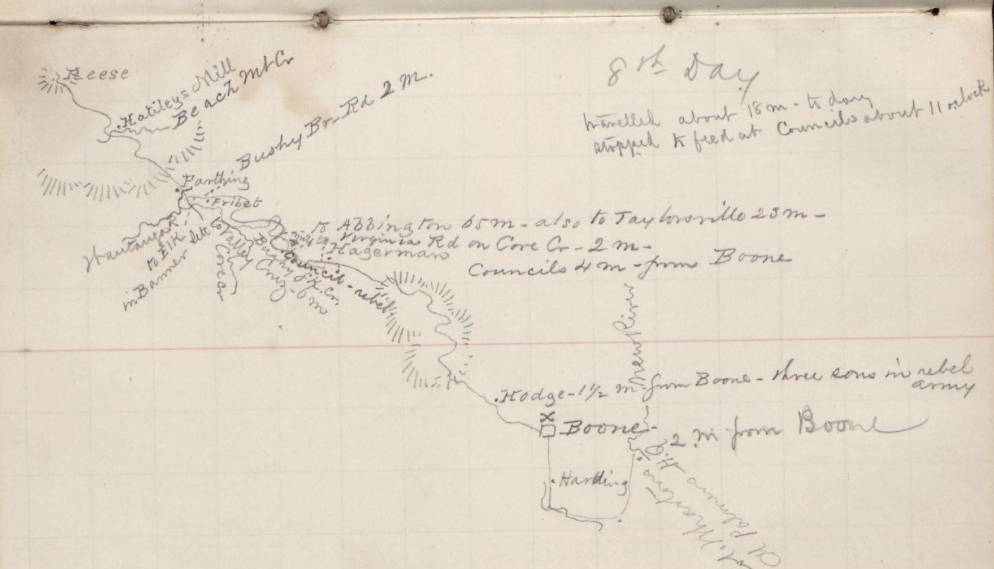

| Sgt. Angelo Wiser's map shows Stoneman's march from Wilkesboro to Jonesville via the south bank of the Yadkin River. |